The following appears in our newest issue of Pitt Dental Medicine magazine.

See the full issue >

By Keightley Amen

Graduates of the University of Pittsburgh School of Dental Medicine can pursue many paths, such as starting a private practice, pursuing specialty training, or earning an additional advanced degree. But many students may not be aware that they also can pursue a rather unique path combining two lanes—dental medicine and military service.

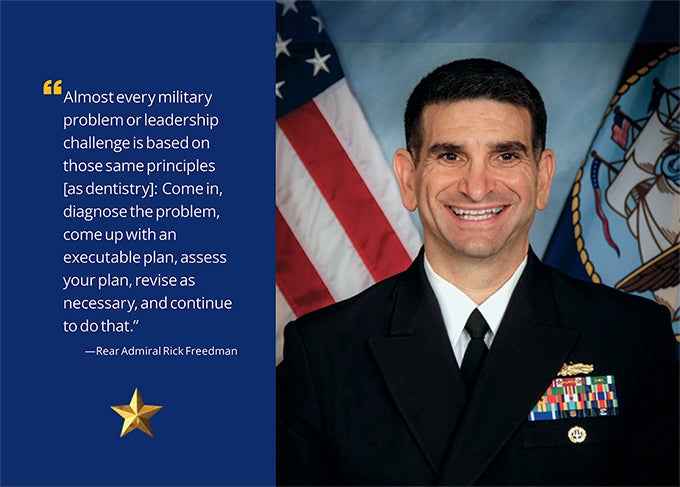

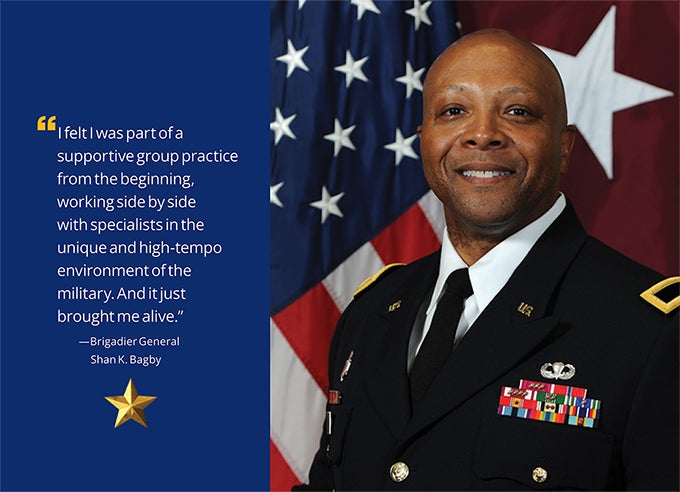

That path has been exceptionally successful and rewarding for two Pitt Dental Medicine alumni: Rear Admiral Rick Freedman (DMD ’91), chief of the U.S. Navy Dental Corps, and Brigadier General Shan K. Bagby (DMD ’93), chief of the U.S. Army Dental Corps.

It’s a rare coincidence that two people from the same program at the same educational institution have such high-level, parallel roles in two different branches of the U.S. military. But these two leaders say they’ve reached such lofty positions thanks, in large part, to the preparation and support they received during their time studying dental medicine at Pitt.

“The practice pattern for dentistry is uniquely suited for military leadership environments. Dentists are trained to work in stressful environments and frequently deal with complex, emergent situations. You have to quickly get a sense of the problem, consider different diagnoses, then develop a plan to take care of the problem—sometimes on the spot. Then you have to execute that plan, oftentimes in a very compressed time frame. And, afterward, you have to perform ongoing assessment and reassessment to make sure that you’ve achieved your objectives,” Freedman says. “Almost every military problem or leadership challenge is based on those same principles: Come in, diagnose the problem, come up with an executable plan, assess your plan, revise as necessary, and continue to do that.”

Serving Those Who Serve

As chiefs of their respective dental corps, Bagby and Freedman are responsible for training, organizing, equipping, educating, and assigning dental officers throughout the world to serve members of the military and their families.

“We exist as part of the covenant between the military and the American people, who send their kids, husbands, wives, sisters, and brothers into service and potentially into harm’s way, knowing that if something should happen to them, there’s a medical care system that stands ready to take care of them regardless of whether or not they can pay,” Bagby says.

Freedman adds: “We ask our people to do very challenging things in defense of freedom and [in] defense of our nation. Being part of a medical system that provides hope to our war fighters, who often are called to go into harm’s way … we provide an assurance that if they were to become wounded, we’d be there for them. I don’t think there could be a more fulfilling mission.”

As part of their roles, both also advise their respective chiefs of operations and surgeons general. Bagby is stationed at Joint Base San Antonio in Texas but travels extensively to military hospitals, clinics, and stand-alone facilities under his supervision, which are spread throughout the country. Freedman is based at the Pentagon in Washington, D.C., and works on the development of future Navy expeditionary medical systems.

Throughout their military careers, they’ve also practiced dentistry in unique and challenging environments, such as on deployments to Iraq and Afghanistan, in extreme temperatures, and on humanitarian missions to locations with limited equipment and facilities.

Freedman jokes: “You haven’t lived ’til you try to practice dentistry aboard a pitching and rolling ship. It’s all about a wide stance and making sure the chair doesn’t move.”

Developing a Dual Career

Bagby and Freedman both chose dentistry because, during their childhoods, they met people in the field who exposed them to its possibilities. But neither intended for the military to be a long-term gig.

“I grew up in an economically disadvantaged environment, and I didn’t have a lot of role models,” Bagby explains. “But I knew I didn’t want to be poor, and I knew I was smart enough to do something better than my circumstances and my environment showed me.”

He met an oral surgeon who volunteered at a local community health clinic, and their interactions inspired his future choices. “I said to myself, ‘I can do that.’ It’s one of the reasons I feel it’s very important to be an example for others—because it’s very difficult for young people to believe that they can be something they’ve never seen.”

Bagby used an ROTC (Reserve Officers’ Training Corps) scholarship to pursue a bachelor’s degree in physics from Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey. He then went on to dental school at the University of Pittsburgh, simultaneously fulfilling his duties in the U.S. Army Reserve and working part time as a home health aide, a time he describes as “frenetic” but essential to becoming the person he is today.

“I had no intention of making the military a career. It was, for me, just an experience at the time. But I enjoyed the camaraderie, the environment of working on a team. And I did not want to go into private practice right away. I wanted to get my skills up,” he explains. “Then I discovered that staying in the military would provide me [with] opportunities to get a more advanced education. The military offered me opportunities that I essentially felt were in line with my values and my skill sets and my personality. And so I’ve stayed.”

Those opportunities included residency training at Martin Luther King Jr./Drew Medical Center in Los Angeles, fellowship training in oral and maxillofacial trauma surgery at the University of Texas Health Science Center in Houston, and two master’s degrees (one in health care administration from Baylor University and one in strategic studies from the U.S. Army War College).

Freedman had a somewhat similar experience, unexpectedly choosing military service.

While attending the University of Pittsburgh for his undergraduate studies in biology, he knew he wanted to pursue dentistry. “Pitt offered so many opportunities and made it so seamless that we could get involved as undergrads. As a student in the Dental Study Club, we got to go to the dental laboratory, work with handpieces, make impressions and models, actually do simulated restorations, and talk to dental students and faculty,” he says. “But the military piece was somewhat of a surprise.”

During his second year of dental school, “A recruiter visited and explained the exciting opportunities for group practice, mentorship, education, [and] financial opportunities with scholarships and stipends, not to mention some really incredible duty stations. … I have family with deep military ties, but I didn’t see myself serving in it until I had that interaction with that recruiter. And there were so many faculty at Pitt who were either former military or were still serving in the reserves, and I really had great opportunities to sit down with them and learn about their experiences.”

His original plan was to serve for four years, learn more, and then go into private practice. “I felt I was part of a supportive group practice from the beginning, working side by side with specialists in the unique and high-tempo environment of the military. And it just brought me alive.”

He stayed, too, taking advantage of continuous educational opportunities and the associated upward mobility, including completing a two-year residency, becoming involved in professional dental associations, earning a master’s degree in health sciences from George Washington University, and achieving a certificate in comprehensive dentistry from the Naval Postgraduate Dental School.

Lessons Learned

As their careers advanced, both men were deployed, then came home to manage dental clinics and then entire hospitals and networks of hospitals. Now they’re responsible for thousands of health care professionals caring for millions of American service members in addition to billion-dollar budgets.

Separately, both men describe the key to their success with the exact same phrase: “Bloom where you’re planted.”

Bagby emphasizes the importance of being true to who you are and taking time for self-reflection and understanding why you do what you do. “Where I’ve thrived is in the understanding that technical abilities are important, but only to the degree that you’re able to meet the needs of others. I can teach anybody how to remove a third molar, but I can’t teach you how to care about the person in the chair,” he says. “So you have to be good at your craft, but you also have to know how to work with other people, to work as part of a team.”

Freedman says that his Pitt education is a major reason he was able to grow into his national leadership role, developing the medical systems of the future and supporting health care professionals in the military so they can be successful at saving lives in the future.

“I look back at the faculty of Pitt Dental Medicine and all the things that now we espouse and that we have names for: evidence-based education, high-velocity learning, covenant leadership—these are things Pitt was doing back then. The faculty at the school gave me a strong foundation of didactic work. It was incredibly collaborative and supportive,” Freedman says. “At the time, I didn’t know that’s how they were shaping me, and I didn’t know how it would influence my professional and leadership style. But it really was a profound experience. The instructors work to make sure they get the best out of you and then sometimes see more in you than you saw in yourself at the time.”